Britney Spears

This article is currently protected from editing. See the protection policy and protection log for more details. Please discuss any changes on the talk page; you may submit an edit request to ask an administrator to make an edit if it is uncontroversial or supported by consensus. You may also request that this page be unprotected. |

Britney Spears | |

|---|---|

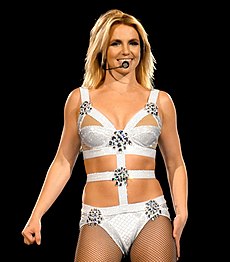

Spears in 2013 | |

| Born | Britney Jean Spears December 2, 1981 McComb, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Education | |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1992–present |

| Works | |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 2 |

| Parent(s) | Jamie Spears Lynne Spears |

| Relatives |

|

| Awards | Full list |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | |

| Instruments | Vocals |

| Labels | |

| Formerly of | Innosense |

| Website | www.britneyspears.com |

| Signature | |

| |

Britney Jean Spears (born December 2, 1981) is an American singer and songwriter. Often referred to as the "Princess of Pop", she is credited with influencing the revival of teen pop during the late 1990s and early 2000s. Spears has sold over 100 million records worldwide, including over 70 million in the United States, making her one of the world's best-selling music artists.[2][3] She has earned numerous awards and accolades, including a Grammy Award, 15 Guinness World Records, six MTV Video Music Awards, seven Billboard Music Awards (including the Millennium Award), the inaugural Radio Disney Icon Award, and a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Her heavily choreographed videos earned her the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award.

After appearing in stage productions and television series, Spears signed with Jive Records in 1997 at age fifteen. Her first two studio albums, ...Baby One More Time (1999) and Oops!... I Did It Again (2000), are among the best-selling albums of all time and made Spears the best-selling teenage artist of all time. With first-week sales of over 1.3 million copies, Oops!... I Did It Again held the record for the fastest-selling album by a female artist in the United States for fifteen years. Spears adopted a more mature and provocative style for her albums Britney (2001) and In the Zone (2003), and starred in the 2002 film Crossroads. She was executive producer of her fifth studio album Blackout (2007), often referred to as her best work.[4] Following a series of highly publicized personal problems, promotion for the album was limited, and Spears was involuntarily placed in a conservatorship.

Subsequently, Spears released the chart-topping albums, Circus (2008) and Femme Fatale (2011), the latter of which became her most successful era of singles in the US charts. With "3" in 2009 and "Hold It Against Me" in 2011, Spears became the second artist after Mariah Carey in the Billboard Hot 100's history to debut at number one with two or more songs. She embarked on a four-year concert residency, Britney: Piece of Me, at Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino in Las Vegas to promote her next two albums Britney Jean (2013) and Glory (2016). In 2019, Spears's legal battle over her conservatorship became more publicized and led to the establishment of the #FreeBritney movement.[5] In 2021, the conservatorship was terminated following her public testimony in which she accused her management team and family of abuse.[6]

In the United States, Spears is the fourth best-selling female album artist of the Nielsen SoundScan era,[7] as well as the best-selling female album artist of the 2000s.[8][9][10] She was ranked by Billboard as the eighth-biggest artist of the 2000s.[11] The singer has amassed six number-one albums on the Billboard 200[12] and five number-one singles on the US Billboard Hot 100: "...Baby One More Time", "Womanizer", "3", "Hold It Against Me", and "S&M (Remix)". Other hit singles include "Oops!... I Did It Again", "Toxic", and "I'm a Slave 4 U". "...Baby One More Time" was named the greatest debut single of all time by Rolling Stone in 2020. In 2004, Spears launched a perfume brand with Elizabeth Arden, Inc.; sales exceeded $1.5 billion as of 2012[update].[13] Forbes has reported Spears as the highest-earning female musician of 2001 and 2012.[14][15] By 2012, she had topped Yahoo!'s list of most searched celebrities seven times in twelve years.[16] Time named Spears one of the 100 most influential people in the world in 2021, while also winning the reader poll by receiving the highest number of votes.[17][18]

Life and career

1981–1997: Early life and career beginnings

Britney Jean Spears was born on December 2, 1981, in McComb, Mississippi,[19] the second child of James "Jamie" Parnell Spears and Lynne Irene Bridges.[20] Her maternal grandmother, Lillian Portell, was English (born in London), and one of Spears's maternal great-great-grandfathers was Maltese.[21] Her siblings are Bryan James Spears and Jamie Lynn Spears.[22] Born in the Bible Belt, where socially conservative evangelical Protestantism is a particularly strong religious influence,[23] she was baptized as a Southern Baptist and sang in a church choir as a child.[24] As an adult, she has studied Kabbalist teachings.[25] On August 5, 2021, Spears announced that she had converted to Catholicism. Her mother, sister, and nieces Maddie Aldridge and Ivey Joan Watson, are also Catholic.[26] However, on September 5, 2022, after Spears's ex-husband, Kevin Federline, and youngest son did an interview defending her father's actions during her conservatorship, she stated: "I don't believe in God anymore because of the way my children and my family have treated me. There is nothing to believe in anymore. I'm an atheist y'all".[27]

At age three, Spears began attending dance lessons in her hometown of Kentwood, Louisiana, and was selected to perform as a solo artist at the annual recital. Aged five she made her local stage debut, singing "What Child Is This?" at her kindergarten graduation. During her childhood, she also had gymnastics and voice lessons, and won many state-level competitions and children's talent shows.[28][29][30] In gymnastics, Spears attended Béla Károlyi's training camp.[31] She said of her ambition as a child, "I was in my own world, ... I found out what I'm supposed to do at an early age".[29]

When Spears was eight, she and her mother Lynne traveled to Atlanta, Georgia, to audition for the 1990s revival of The Mickey Mouse Club. Casting director Matt Casella rejected her as too young, but introduced her to Nancy Carson, a New York City talent agent. Carson was impressed with Spears's singing and suggested enrolling her at the Professional Performing Arts School; shortly afterward, Lynne and her daughters moved to a sublet apartment in New York.[citation needed]

Spears was hired for her first professional role as the understudy for the lead role of Tina Denmark in the off-Broadway musical Ruthless! She also appeared as a contestant on the popular television show Star Search and was cast in a number of commercials.[32][33] In December 1992, she was cast in The Mickey Mouse Club alongside Christina Aguilera, Justin Timberlake, Ryan Gosling, and Keri Russell. After the show was canceled in 1994, she returned to Mississippi and enrolled at McComb's Parklane Academy. Although she made friends with most of her classmates, she compared the school to "the opening scene in Clueless with all the cliques. ... I was so bored. I was the point guard on the basketball team. I had my boyfriend, and I went to homecoming and Christmas formal. But I wanted more."[29][34]

In June 1997, Spears was in talks with manager Lou Pearlman to join the female pop group Innosense. Lynne asked family friend and entertainment lawyer Larry Rudolph for his opinion and submitted a tape of Spears singing over a Whitney Houston karaoke song along with some pictures. Rudolph decided that he wanted to pitch her to record labels, for which she needed a professional demo made. He sent Spears an unused song of Toni Braxton; she rehearsed for a week and recorded her vocals in a studio. Spears traveled to New York with the demo and met with executives from four labels, returning to Kentwood the same day. Three of the labels rejected her, saying that audiences wanted pop bands such as the Backstreet Boys and the Spice Girls, and "there wasn't going to be another Madonna, another Debbie Gibson, or another Tiffany."[35]

Two weeks later, executives from Jive Records returned calls to Rudolph.[35] Senior vice president of A&R Jeff Fenster said about Spears's audition that "it's very rare to hear someone that age who can deliver emotional content and commercial appeal ... For any artist, the motivation—the 'eye of the tiger'—is extremely important. And Britney had that."[29] Spears sang Houston's "I Have Nothing" (1992) for the executives, and was subsequently signed to the label.[36] They assigned her to work with producer Eric Foster White for a month; he reportedly shaped her voice from "lower and less poppy" delivery to "distinctively, unmistakably Britney".[37] After hearing the recorded material, president Clive Calder ordered a full album. Spears had originally envisioned "Sheryl Crow music, but younger; more adult contemporary". She felt secure with her label's appointment of producers, since "It made more sense to go pop, because I can dance to it—it's more me."[29] She flew to Cheiron Studios in Stockholm, Sweden, where half of the album was recorded from March to April 1998, with producers Max Martin, Denniz Pop, and Rami Yacoub, among others.[29]

1998–2000: ...Baby One More Time and Oops!... I Did It Again

After Spears returned to the United States, she embarked on a shopping mall promotional tour, titled L'Oreal Hair Zone Mall Tour, to promote her upcoming debut album. Her show was a four-song set and she was accompanied by two back-up dancers. Her first concert tour followed, as an opening act for NSYNC.[38] Her debut studio album, ...Baby One More Time, was released on January 12, 1999.[29] It debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard 200 and was certified two-times platinum by the Recording Industry Association of America after a month. Worldwide, the album topped the charts in fifteen countries and sold over 10 million copies in a year.[39] It became the biggest-selling album ever by a teenage artist.[30]

"...Baby One More Time" was released as the lead single from the album. Originally, Jive Records wanted its music video to be animated; however, Spears rejected it, and suggested the final concept of a Catholic schoolgirl.[37] The single sold 500,000 copies on its first day, and peaked at number one on the Billboard Hot 100, topping the chart for two consecutive weeks. It has sold more than 10 million copies, making it one of the best-selling singles of all time.[40][41] "...Baby One More Time" later received a Grammy nomination for Best Female Pop Vocal Performance.[42] The title track also topped the singles chart for two weeks in the United Kingdom, and became the fastest-selling single ever by a female artist, shipping over 460,000 copies.[43] It would later become the 25th-most successful song of all time in British chart history.[44] Spears is the youngest female artist to have a million seller in the UK.[45] The album's third single "(You Drive Me) Crazy" became a top-ten hit worldwide and further propelled the success of the ...Baby One More Time album. The album has sold 25 million copies worldwide,[46][47] making it one of the best-selling albums of all time. It is the best-selling debut album by any artist.[48][49]

On June 28, 1999, Spears began her first headlining ...Baby One More Time Tour in North America, which was positively received by critics.[50] It also generated some controversy due to her racy outfits.[51] An extension of the tour, titled (You Drive Me) Crazy Tour, followed in March 2000. Spears premiered songs from her upcoming second album during the show.[34]

Oops!... I Did It Again, Spears's second studio album, was released in May 2000. It debuted at number one in the US, selling 1.3 million copies, breaking the Nielsen SoundScan record for the highest debut sales by any solo artist.[52] It has sold over 20 million copies worldwide to date,[53] making it one of the best-selling albums of all time. Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone said that "the great thing about Oops! – under the cheese surface, Britney's demand for satisfaction is complex, fierce and downright scary, making her a true child of rock & roll tradition."[54] The album's lead single, "Oops!... I Did It Again", peaked at the top of the charts in Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and many other European nations,[45][55] while the second single "Lucky", peaked at number one in Austria, Germany, Sweden, and Switzerland. The album as well as the title track received Grammy nominations for Best Pop Vocal Album and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance, respectively.[56]

The same year, Spears embarked on the Oops!... I Did It Again Tour, which grossed $40.5 million; she also released her first book, Britney Spears' Heart to Heart, co-written with her mother.[30][57] On September 7, 2000, Spears performed at the 2000 MTV Video Music Awards. Halfway through the performance, she ripped off her black suit to reveal a sequined flesh-colored bodysuit, followed by heavy dance routine. It is noted by critics as the moment that Spears showed signs of becoming a more provocative performer.[58] Amidst media speculation, Spears confirmed she was dating NSYNC member Justin Timberlake.[30] Spears and Timberlake both graduated from high school via distance learning from the University of Nebraska High School.[59][60] She also bought a home in Destin, Florida.[61]

2001–2002: Britney and Crossroads

In January 2001, Spears hosted the 28th Annual American Music Awards, starred at Rock in Rio alongside NSYNC, and performed as a special guest in the Super Bowl XXXV halftime show headlined by Aerosmith and NSYNC.[62][63] In February 2001, she signed a $7–8 million promotional deal with Pepsi, and released another book co-written with her mother, titled A Mother's Gift.[30] Her self-titled third studio album, Britney, was released in November 2001. While on tour, she felt inspired by hip hop artists such as Jay-Z and The Neptunes and wanted to create a record with a funkier sound.[64] The album debuted at number one in the Billboard 200 and reached top five positions in Australia, the United Kingdom, and mainland Europe, and has sold 10 million copies worldwide.[45][65][66]

Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic called Britney "the record where she strives to deepen her persona, making it more adult while still recognizably Britney. ... It does sound like the work of a star who has now found and refined her voice, resulting in her best record yet."[67] The album was honored with two Grammy nominations—Best Pop Vocal Album and Best Female Pop Vocal Performance for "Overprotected"—and was listed in 2007 as one of Entertainment Weekly's "100 Best Albums from the Past 25 Years".[68][69] The album's lead single, "I'm a Slave 4 U", became a top ten hit worldwide.[70]

Spears's performance of the single at the 2001 MTV Video Music Awards featured a caged tiger (wrangled by Bhagavan Antle) and a large albino python draped over her shoulders.[71] It was harshly received by animal rights organization PETA, who claimed the animals were mistreated and scrapped plans for an anti-fur billboard that was to feature Spears.[58] Jocelyn Vena of MTV summarized Spears's performance at the ceremony, saying, "draping herself in a white python and slithering around a steamy garden setting – surrounded by dancers in zebra and tiger outfits – Spears created one of the most striking visuals in the 27-year history of the show."[72]

To support the album, Spears embarked on the Dream Within a Dream Tour. The show was critically praised for its technical innovations, the pièce de résistance being a water screen that pumped two tons of water into the stage.[73][74] The tour grossed $43.7 million, becoming the second highest-grossing tour of 2002 by a female artist, behind Cher's Farewell Tour.[75] Her career success was highlighted by Forbes in 2002, as Spears was ranked the world's most powerful celebrity.[76] Spears also landed her first starring role in Crossroads, released in February 2002. Although the film was largely panned, critics praised Spears's acting and the film was a box office success.[77][78][79] Crossroads, which had a $12 million budget, went on to gross over $61.1 million worldwide.[79]

In June 2002, Spears opened her first restaurant, Nyla, in New York City, but terminated her relationship in November, citing mismanagement and "management's failure to keep her fully apprised".[80] In July 2002, Spears announced she would take a six-month break from her career; however, she went back into the studio in November to record her new album.[81] Spears's relationship with Justin Timberlake ended after three years.[82] In November 2002, Timberlake released the song "Cry Me a River" as the second single from his solo debut album. The music video featured a Spears look-alike and fueled the rumors that she had been unfaithful to him.[83][84] As a response, Spears wrote the ballad "Everytime" with her backing vocalist and friend Annet Artani.[85] The same year, Limp Bizkit frontman Fred Durst said that he was in a relationship with Spears. However, Spears denied Durst's claims. In a 2009 interview, he explained that "I just guess at the time it was taboo for a guy like me to be associated with a gal like her."[86]

2003–2005: In the Zone and first two marriages

In August 2003, Spears opened the MTV Video Music Awards with Christina Aguilera, performing "Like a Virgin". Halfway through they were joined by Madonna, with whom they both kissed. The incident was highly publicized. In 2008, MTV listed the performance as the number-one opening moment in the history of MTV Video Music Awards,[87] while Blender magazine cited it as one of the twenty-five sexiest music moments on television history.[88] Spears released her fourth studio album, In the Zone, in November 2003. She assumed more creative control by writing and co-producing most of the material.[30] Vibe called it "A supremely confident dance record that also illustrates Spears's development as a songwriter."[89]

NPR listed the album as one of "The 50 Most Important Recording of the Decade", adding that "the decade's history of impeccably crafted pop is written on her body of work."[90] In the Zone sold over 609,000 copies in the United States during its first week of availability in the United States, debuting at the top of the charts, making Spears the first female artist in the SoundScan era to have her first four studio albums to debut at number one.[30] It also debuted at the top of the charts in France and the top ten in Belgium, Denmark, Sweden, and the Netherlands.[91] The album produced four singles: "Me Against the Music", a collaboration with Madonna; "Toxic"—which won Spears her first Grammy for Best Dance Recording; "Everytime", and "Outrageous".[30]

In January 2004, Spears married childhood friend Jason Allen Alexander at A Little White Wedding Chapel in Las Vegas, Nevada. The marriage was annulled 55 hours later, following a petition to the court that stated that Spears "lacked understanding of her actions".[92]

In March 2004, she embarked on The Onyx Hotel Tour in support of In the Zone.[93] In June 2004, Spears fell and injured her left knee during the music video shoot for "Outrageous". Spears underwent arthroscopic surgery. She was forced to remain six weeks with a thigh brace, followed by eight to twelve weeks of rehabilitation, which caused The Onyx Hotel Tour to be canceled.[94] During 2004, Spears became involved in the Kabbalah Centre through her friendship with Madonna.[95]

In July 2004, Spears became engaged to dancer Kevin Federline, whom she had met three months earlier. The romance was the subject of intense media attention, since Federline had recently broken up with actress Shar Jackson, who was still pregnant with their second child at the time.[30] The stages of their relationship were chronicled in Spears's first reality show Britney and Kevin: Chaotic, which premiered on May 17, 2005, on UPN. Spears later referred to the show in a 2013 interview as "probably the worst thing I've done in my career".[96] They held a wedding ceremony on September 18, 2004, but were not legally married until three weeks later on October 6 due to a delay finalizing the couple's prenuptial agreement.[97]

Shortly after, she released her first perfume, Curious, with Elizabeth Arden, which broke the company's first-week gross for a perfume.[30] In October 2004, Spears took a career break to start a family.[98] Greatest Hits: My Prerogative, her first greatest hits compilation album, was released in November 2004.[99] Spears's cover version of Bobby Brown's "My Prerogative" was released as the lead single from the album, reaching the top of the charts in Finland, Ireland, Italy, and Norway.[100] The second single, "Do Somethin'", was a top ten hit in Australia, the United Kingdom, and other countries of mainland Europe.[101][102] In August 2005, Spears released "Someday (I Will Understand)", which was dedicated to her first child, a son named Sean Preston, who was born the following month.[103] In November 2005, she released her first remix compilation, B in the Mix: The Remixes, which consists of 11 remixes.[104]

2006–2007: Personal struggles and Blackout

In February 2006, pictures surfaced of Spears driving with her son, Sean, on her lap instead of in a car seat. Child advocates were horrified by the photos of her holding the wheel with one hand and Sean with the other. Spears claimed that the situation happened because of a frightening encounter with paparazzi, and that it was a mistake on her part.[30] The following month, she guest-starred on the Will & Grace episode "Buy, Buy Baby" as closeted lesbian Amber-Louise.[105] She announced she no longer studied Kabbalah in May 2006, explaining, "my baby is my religion".[95] Spears posed nude for the August 2006 cover of Harper's Bazaar; the photograph was compared to Demi Moore's August 1991 Vanity Fair cover.[30] In September 2006, she gave birth to her second son, Jayden James.[106] In November 2006, Spears filed for divorce from Federline, citing irreconcilable differences.[107] Their divorce was finalized in July 2007, when the two reached a global settlement and agreed to share joint custody of their sons.[108]

Spears's maternal aunt Sandra Bridges Covington, with whom she had been very close, died of ovarian cancer in January 2007.[109] In February, Spears stayed in a drug rehabilitation facility in Antigua for less than a day. The following night, she shaved her head with electric clippers at a hair salon in Tarzana, Los Angeles. She admitted herself to other treatment facilities during the following weeks.[110] In May 2007, she produced a series of promotional concerts at House of Blues venues, titled The M+M's Tour.[111] In October 2007, Spears lost physical custody of her sons to Federline. The reasons of the court ruling were not revealed to the public.[112] Spears was also sued by Louis Vuitton over her 2005 music video "Do Somethin'" for upholstering her Hummer interior in counterfeit Louis Vuitton cherry blossom fabric, which resulted in the video being banned on European TV stations.[113]

In October 2007, Spears released her fifth studio album, Blackout. The album debuted atop the charts in Canada and Ireland, at number two in the U.S. Billboard 200, France, Japan, Mexico, and the United Kingdom, and the top ten in Australia, South Korea, New Zealand, and many European nations. In the United States, it was Spears's first album not to debut at number one, although, she did become the only female artist to have her first five studio albums debut at the two top slots of the chart.[114] The album received positive reviews from critics and had sold 3.1 million copies worldwide by the end of 2008.[115][116] Blackout won Album of the Year at the 2008 MTV Europe Music Awards and was listed as the fifth Best Pop Album of the Decade by The Times.[117][118]

Spears performed the lead single "Gimme More" at the 2007 MTV Video Music Awards. The performance was widely panned by critics.[119] Despite the criticism, the single enjoyed worldwide success, peaking at number one in Canada and within the top ten in almost every country it charted.[120][121] The second single "Piece of Me" reached the top of the charts in Ireland and reached the top five in Australia, Canada, Denmark, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. The third single "Break the Ice" was released the following year,[122] and respectively reached numbers seven and nine in Ireland and Canada.[123][124] In December 2007, Spears began a relationship with paparazzo Adnan Ghalib.[125]

2008–2010: Conservatorship and Circus

In January 2008, Spears refused to relinquish custody of her sons to Federline's representatives. She was hospitalized at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center after police that had arrived at her house noted she appeared to be under the influence of an unidentified substance. The following day, Spears's visitation rights were suspended at an emergency court hearing, and Federline was given sole physical and legal custody of their sons. She was committed to the psychiatric ward of Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center and put on 5150 involuntary psychiatric hold under California state law. The court placed her under a conservatorship led by her father, Jamie Spears, and attorney Andrew Wallet, giving them complete control of her assets.[30][126] She was released five days later.[127][128]

The following month, Spears guest-starred on the How I Met Your Mother episode "Ten Sessions" as receptionist Abby. She received positive reviews for her performance, as well as bringing the series its highest ratings ever.[129][130] In July 2008, Spears regained some visitation rights after coming to an agreement with Federline and his counsel.[131] In September 2008, Spears opened the MTV Video Music Awards with a pre-taped comedy sketch with Jonah Hill and an introduction speech. She won Best Female Video, Best Pop Video, and Video of the Year for "Piece of Me".[132] A 60-minute introspective documentary, Britney: For the Record, was produced to chronicle Spears's return to the recording industry. Directed by Phil Griffin, For the Record was shot in Beverly Hills, Hollywood, and New York City during the third quarter of 2008.[133] The documentary was broadcast on MTV to 5.6 million viewers for the two airings on the premiere night. It was the highest rating in its Sunday night timeslot and in the network's history.[134]

In December 2008, Spears's sixth studio album Circus was released. It received positive reviews from critics[135] and debuted at number one in Canada, Czech Republic, and the United States, and within the top ten in many European nations.[121][136] In the United States, Spears became the youngest female artist to have five albums debut at number one, earning a place in Guinness World Records.[137] She also became the only act in the SoundScan era to have four albums debut with 500,000 or more copies sold.[136] The album was one of the fastest-selling albums of the year,[138] and has sold 4 million copies worldwide.[139] Its lead single, "Womanizer", became Spears's first chart-topper on the Billboard Hot 100 since "...Baby One More Time". The single also topped the charts in Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, Norway, and Sweden.[140][141] It was also nominated for the Grammy Award for Best Dance Recording.[142]

In January 2009, Spears and her father obtained a restraining order against her former manager Sam Lutfi, ex-boyfriend Adnan Ghalib, and attorney Jon Eardley, all of whom had been accused of conspiring to gain control of Spears's affairs.[143] Spears embarked on The Circus Starring Britney Spears tour in March 2009. With a gross of U.S. $131.8 million, it became the fifth highest-grossing tour of the year.[144] In November 2009, Spears released her second greatest hits album, The Singles Collection. The album's lead and only single, "3", became her third number-one single in the U.S.[145]

In May 2010, Spears's representatives confirmed she was dating her agent, Jason Trawick, and that they had decided to end their professional relationship to focus on their personal relationship.[146] Spears designed a limited edition clothing line for Candie's, which was released in stores in July 2010.[147] In September 2010, she made a cameo appearance on a Spears-themed tribute episode of the television series Glee, titled "Britney/Brittany"; the episode drew the highest Nielsen rating – up to that point in the series's run[148] – in the 18–49 demographic.[149][150]

2011–2012: Femme Fatale and The X Factor

In March 2011, Spears released her seventh studio album, Femme Fatale.[151] The album peaked at number one in the United States, Canada, and Australia, and within the top ten on nearly every other chart. Its peak in the United States tied Spears with Mariah Carey and Janet Jackson for the third-most number ones among women.[12] Femme Fatale has been certified platinum by the RIAA and as of February 2014, it had sold 2.4 million copies worldwide.[152][153]

The album's lead single, "Hold It Against Me" debuted atop the Billboard Hot 100, becoming Spears's fourth number-one single on the chart and making her the second artist in history to have two consecutive singles debut at number one, after Mariah Carey.[154] The second single "Till the World Ends" peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100 in May,[155] while the third single "I Wanna Go" reached number seven in August. Femme Fatale became Spears's first album in which three of its songs reached the top ten of the chart. The fourth and final single "Criminal" was released in September 2011. The music video sparked controversy when British politicians criticized Spears for using replica guns while filming the video in a London area that had been badly affected by the 2011 England riots.[156] Spears's management briefly responded, stating, "The video is a fantasy story featuring Britney's boyfriend, Jason Trawick, which literally plays out the lyrics of a song written three years before the riots ever happened."[157] In April 2011, Spears appeared in a remix of Rihanna's song "S&M".[158] It reached number one in the US later that month, giving Spears her fifth number one on the chart.[159] On Billboard's 2011 Year-End list, Spears was ranked number fourteen on the Artists of the Year,[160] thirty-two on Billboard 200 artists, and ten on Billboard Hot 100 artists.[161][162] Spears co-wrote "Whiplash", a song from the album When the Sun Goes Down (2011) by Selena Gomez & the Scene.[163]

In June 2011, Spears embarked on her Femme Fatale Tour.[164] The first ten dates of the tour grossed $6.2 million, landing the fifty-fifth spot on Pollstar's Top 100 North American Tours list for the half-way point of the year.[165] The tour ended on December 10, 2011, in Puerto Rico after 79 performances.[166] A DVD of the tour was released in November 2011.[167] In August 2011, Spears received the Michael Jackson Video Vanguard Award at the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards.[168] The next month, she released her second remix album, B in the Mix: The Remixes Vol. 2.[169] In December 2011, Spears became engaged to her long-time boyfriend Jason Trawick, who had formerly been her agent.[170] Trawick was legally granted a role as co-conservator, alongside her father, in April 2012.[171]

In May 2012, Spears was hired to replace Nicole Scherzinger as a judge for the second season of the U.S. version of The X Factor, joining Simon Cowell, L.A. Reid, and fellow new judge Demi Lovato, who replaced Paula Abdul. With a reported salary of $15 million, she became the highest-paid judge on a singing competition series in television history.[172] However, Katy Perry broke her record in 2018 after Perry was signed for a $25-million salary to serve as a judge on ABC's revival of American Idol.[173][174] Spears mentored the Teens category; her final act, Carly Rose Sonenclar, was named the runner-up of the season. Spears did not return for the show's third season.[175]

Spears appeared on the song "Scream & Shout" with will.i.am, which was released as the third single from his fourth studio album, #willpower (2013). The song later became Spears's sixth number one single on the UK Singles Chart and peaked at number three on the Billboard Hot 100. "Scream & Shout" was among the best-selling songs of 2012 and 2013 with denoting sales of over 8.1 million worldwide,[176] the accompanying music video was the third most-viewed video in 2013 on Vevo despite the video being released in 2012.[177][failed verification] In December 2012, Forbes named her music's top-earning woman of 2012, with estimated earnings of $58 million.[178]

2013–2015: Britney Jean and Britney: Piece of Me

Spears began work on her eighth studio album, Britney Jean, in December 2012,[179] and enlisted will.i.am as its executive producer in May 2013.[180] In January 2013, Spears and Jason Trawick ended their engagement. Trawick was also removed as Spears's co-conservator, restoring her father as the sole conservator.[181][182] Following the breakup, she began dating David Lucado in March; the couple split in August 2014.[183] During the production of Britney Jean, Spears recorded the song "Ooh La La" for the soundtrack of The Smurfs 2, which was released in June 2013.[184]

On September 17, 2013, she appeared on Good Morning America to announce her two-year concert residency at Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino in Las Vegas, titled Britney: Piece of Me. It began on December 27, 2013, and included a total of 100 shows throughout 2014 and 2015.[185][186] During the same appearance, Spears announced that Britney Jean would be released on December 3, 2013, in the United States.[187][188] It was released through RCA Records due to the disbandment of Jive Records in 2011, which had formed the joint RCA/Jive Label Group (initially known as BMG Label Group) between 2007 and 2011.[189]

Britney Jean became Spears's final project under her original recording contract with Jive, which had guaranteed the release of eight studio albums.[190] The record received a low amount of promotion and had little commercial impact, reportedly due to time conflicts involving preparations for Britney: Piece of Me.[191] Upon its release, the record debuted at number four on the U.S. Billboard 200 with first-week sales of 107,000 copies, becoming her lowest-peaking and lowest-selling album in the United States.[192] Britney Jean debuted at number 34 on the UK Albums Chart, selling 12,959 copies in its first week. In doing so, it became Spears's lowest-charting and lowest-selling album in the country.[193]

"Work Bitch" was released as the lead single from Britney Jean in September 2013.[194] It debuted and peaked at number 12 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100 marking Spears's 31st entry on the chart and the fifth highest debut of her career on the chart, and her seventh in the top 20. It also marked Spears's 19th top 20 entry and overall her 23rd top 40 single. The song marked Spears's highest sales debut since her 2011 number-one single "Hold It Against Me". "Work Bitch" debuted and peaked at number seven on the UK Singles Chart. The song also peaked within the top ten of the charts in Brazil, Canada, France, Italy, Mexico, and Spain.[195]

The second single "Perfume" premiered in November 2013.[196][197] It debuted and peaked at number 76 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.[198] In October 2013, she was featured as a guest vocalist on the song "SMS (Bangerz)" by Miley Cyrus, from the latter's fourth studio album Bangerz (2013).[199] On January 8, 2014, Spears won Favorite Pop Artist at the 40th People's Choice Awards at the Microsoft Theater in Los Angeles.[200] In August 2014, Spears confirmed she had renewed her contract with RCA and that she was writing and recording new music for her next album.[201]

Spears announced via Twitter in August 2014 that she would be releasing an intimate apparel line called "The Intimate Britney Spears". It was available to be purchased beginning on September 9, 2014, in the United States and Canada through Spears's Intimate Collection website. It was later available on September 25 for purchase in Europe. The company now ships to over 200 countries including Australia and New Zealand.[202] On September 25, 2014, Spears confirmed on Good Morning Britain that she had extended her contract with The AXIS and Planet Hollywood Resort & Casino, to continue Britney: Piece of Me for two additional years.[203] Spears began dating television producer Charlie Ebersol in October 2014. The pair were split in June 2015.[204]

In March 2015, it was confirmed by People magazine that Spears would release a new single, "Pretty Girls", with Iggy Azalea, on May 4, 2015.[205] The song debuted and peaked at number 29 on the Billboard Hot 100 and charted moderately in international territories. Spears and Azalea performed the track live at the 2015 Billboard Music Awards from The AXIS, the home of Spears's residency, to positive critical response. Entertainment Weekly praised the performance, noting "Spears gave one of her most energetic televised performances in years."[206] On June 16, 2015, Giorgio Moroder released his album, Déjà Vu, that featured Spears on "Tom's Diner".[207]

The song was released as the fourth single from the album on October 9, 2015.[208] In an interview, Moroder praised Spears's vocals and said that she did a "good job" with the song and also stated that Spears "sounds so good that you would hardly recognize her."[209][210] At the 2015 Teen Choice Awards, Spears received the Candie's Style Icon Award, her ninth Teen Choice Award.[211] In November 2015, Spears guest-starred as a fictionalized version of herself on The CW series, Jane the Virgin.[212] On the show, she danced to "Toxic" with Gina Rodriguez's character.[213]

2016–2018: Glory, continued residency, and the Piece of Me Tour

In 2016, Spears confirmed via social media that she had begun recording her ninth studio album.[214] On March 1, 2016, V magazine announced that Spears would appear on the cover of its 100th issue, dated March 8, 2016, in addition to revealing three different covers shot by photographer Mario Testino for the milestone publication.[215] Editor-in-chief of the magazine, Stephen Gan, revealed that Spears was selected for the "V100" issue because of her status as an icon in the industry. On the decision, Gan stated, "who in our world did not grow up listening to her music?"[216] In May 2016, Spears launched a casual role-play gaming application titled Britney Spears: American Dream. The app, created by Glu Mobile, was made available through both iOS and Google Play.[217]

On May 22, 2016, Spears performed a medley of her past singles at the 2016 Billboard Music Awards.[218][219] In addition to opening the show, Spears was honored with the Billboard Millennium Award.[220] On July 15, 2016, Spears released the lead single, "Make Me", from her ninth studio album, featuring guest vocals from American rapper G-Eazy.[221] The album, Glory, was formally released on August 26, 2016. On August 16, 2016, MTV and Spears announced that she would perform at the 2016 MTV Video Music Awards.[222] The performance marked Spears's first time returning to the VMA stage after her widely panned performance of "Gimme More" at the 2007 show nine years earlier.[223] Along with "Make Me", Spears and G-Eazy also performed the latter's hit song "Me, Myself & I".[224]

Spears appeared on the cover of Marie Claire UK for the October 2016 issue. In the publication, Spears revealed that she had suffered from crippling anxiety in the past, and that motherhood played a major role in helping her overcome it.[225] "My boys don't care if everything isn't perfect. They don't judge me", Spears said in the issue.[226] In November 2016, during an interview with Las Vegas Blog, Spears confirmed she had already begun work on her next album, stating: "I'm not sure what I want the next album to sound like. ... I just know that I'm excited to get into the studio again and actually have already been back recording."[227] In the same month, she released a remix version of "Slumber Party" as the second single from Glory, featuring Tinashe.[228]

She began dating "Slumber Party"'s music video co-star Sam Asghari after the two met on set.[229] In January 2017, Spears received four wins out of four nominations at the 43rd People's Choice Awards, including Favorite Pop Artist, Female Artist, Social Media Celebrity, as well as Comedic Collaboration for a skit with Ellen DeGeneres for The Ellen DeGeneres Show.[230] In March 2017, Spears announced that her residency concert would be performed abroad as a world tour, Britney: Live in Concert, with dates in select Asian cities.[231][232][233] In April 2017, the Israeli Labor Party announced that it would reschedule its July primary election to avoid conflict with Spears's sold-out Tel Aviv concert, citing traffic, and security concerns.[234]

Spears's manager Larry Rudolph also announced the residency would not be extended following her contract expiration with Caesars Entertainment at the end of 2017. On April 29, 2017, Spears became the first recipient of the Icon Award at the 2017 Radio Disney Music Awards.[235] On November 4, 2017, Spears attended the grand opening of the Nevada Childhood Cancer Foundation Britney Spears Campus in Las Vegas.[236] Later that month, Forbes announced that Spears was the 8th highest earning female musician, earning $34 million in 2017.[237] On December 31, 2017, Spears performed the final show of Britney: Piece of Me.[238] The final performance reportedly brought in $1.172 million, setting a new box office record for a single show in Las Vegas, and breaking the record previously held by Jennifer Lopez.[238] The last show was broadcast live with performances of "Toxic" and "Work Bitch" airing on ABC's Dick Clark's New Year's Rockin' Eve to a record audience of 25.6 million.[239]

In January 2018, Spears released her 24th perfume with Elizabeth Arden, Sunset Fantasy,[240] and announced the Piece of Me Tour which took place in July 2018 in North America and Europe.[241] Tickets were sold out within minutes for major cities, and additional dates were added to meet the demand.[242] Pitbull was the supporting act for the European leg.[243] The tour ranked at 86 and 30 on Pollstar's 2018 Year-End Top 100 Tours chart both in North America and worldwide, respectively. In total, the tour grossed $54.3 million with 260,531 tickets sold and was the sixth highest-grossing female tour of 2018, and was the United Kingdom's second best-selling female tour of 2018.[244][245]

On March 20, 2018, Spears was announced as part of a campaign for French luxury fashion house Kenzo.[246] The company said it aimed to shake up the 'jungle' world of fashion with Spears's 'La Collection Memento No. 2' campaign.[247] On April 12, 2018, Spears was honored with the 2018 GLAAD Vanguard Award at the GLAAD Media Awards for her role in "accelerating acceptance for the LGBTQ community".[248] On April 27, 2018, Epic Rights announced a new partnership with Spears to debut her own fashion line in 2019, which would include clothing, fitness apparel, accessories, and electronics.[249]

In July 2018, Spears released her first unisex fragrance, Prerogative.[250] On October 18, 2018, Spears announced her second Las Vegas residency show, Britney: Domination, which was set to launch at Park MGM's Park Theatre on February 13, 2019.[251] Spears was slated to make $507,000 per show, which would have made her the highest paid act on the Las Vegas Strip.[251][252] On October 21, 2018, Spears performed at the Formula One Grand Prix in Austin, the final performance of her Piece of Me Tour.[253]

2019–2021: Conservatorship dispute, #FreeBritney, and abuse allegations

On January 4, 2019, Spears announced an indefinite hiatus and the cancellation of her Las Vegas residency after her father, Jamie, suffered a near-fatal colon rupture.[254] In March 2019, Andrew Wallet resigned as co-conservator of her estate after 11 years.[255] Spears entered a psychiatric facility amidst stress from her father's illness that same month.[256] The following month, a fan podcast, Britney's Gram, released a voicemail message from a source who claimed to be a former member of Spears's legal team. They alleged that Jamie had canceled the residency due to Spears's refusal to take her medication, that he had been holding her in the facility against her will since January 2019 after she violated a no-driving rule, and that her conservatorship was supposed to have ended in 2009.[257][258] The allegations gave rise to a movement to terminate the conservatorship, #FreeBritney,[259] which received support from celebrities including singers Cher, Paris Hilton, and Miley Cyrus, and the nonprofit organization American Civil Liberties Union.[260][261][262][263] On April 22, 2019, fans protested outside the West Hollywood City Hall and demanded Spears's release.[256] Spears said "all [was] well" two days later and left the facility later that month.[264][265]

In a May 2019 hearing, Judge Brenda Penny ordered a professional evaluation of the conservatorship.[266] In September, Spears's ex-husband Federline obtained a restraining order against Britney's father, Jamie, following an alleged physical altercation between Jamie and one of her sons.[267] Spears's longtime care manager, Jodi Montgomery, temporarily replaced Jamie as her conservator that same month,[268] which also saw a hearing where no decisions about the arrangement were reached.[269] An interactive pop-up museum dedicated to Spears, dubbed "The Zone", opened in Los Angeles in February 2020, though it was later suspended in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.[270][271] She released Glory's Japanese-exclusive bonus track, "Mood Ring" as a single, and debuted a new cover of the album to streaming and digital platforms worldwide in May 2020.[272] In August, Jamie called the #FreeBritney movement "a joke" and its organizers "conspiracy theorists".[273]

On August 17, 2020, Spears's court-appointed lawyer, Samuel D. Ingham III, submitted a court filing that documented Spears's desire to have her conservatorship altered to reflect her wishes as well as lifestyle, to instate Montgomery as her permanent conservator,[274] and to replace Jamie with a fiduciary as conservator of her estate.[275] Four days later, Penny extended the established arrangement until February 2021.[276] In November 2020, Penny approved Bessemer Trust as co-conservator of Spears's estate alongside Jamie.[277] The following month, Spears released a new deluxe edition of Glory, which includes "Mood Ring" and new songs "Swimming in the Stars" and "Matches".[278]

A documentary about Spears's career and conservatorship, Framing Britney Spears, premiered on FX in February 2021.[279] Spears later revealed that she had seen parts of the documentary, stating that she felt humiliated by the perception of her that was presented and that she "cried for two weeks" following the initial broadcast.[280] The following month, Ingham filed a petition to permanently replace Jamie with Montgomery as the conservator of Spears's person,[281] citing a 2014 order that determined that Spears did not have the capacity to consent to medical treatment of any form.[282]

On June 22, 2021, shortly before Spears was set to speak to the court, The New York Times obtained confidential court documents stating that Spears had pushed for years to end her conservatorship.[283] Spears spoke to the court on June 23, calling the conservatorship "abusive". She said she had lied by "telling the whole world I'm OK and I'm happy", and that she was traumatized and angry.[284][285][286] The court statement received widespread media coverage and generated over 1 million shares on Twitter, over 500,000 messages using the tag #FreeBritney, and more than 150,000 messages with a new hashtag referencing the court appearance, #BritneySpeaks.[287][288]

On July 1, Bessemer Trust asked the judge to allow them to withdraw from the conservatorship, saying that they had been misled and had entered into the arrangement on the understanding that the conservatorship was voluntary.[289] The same day, senators Elizabeth Warren and Bob Casey Jr. called on federal agencies to increase oversight of the country's conservatorship systems.[290] Spears's manager of 25 years, Larry Rudolph, resigned on July 6 due to her "intention to officially retire"[291] and on that same day, it was reported that Ingham planned to file documents to the court asking to be dismissed.[292] In a July 14 hearing, Judge Penny approved the resignations of Bessemer Trust and Ingham. The court also approved of Spears's request to hire attorney Mathew S. Rosengart to represent her. Rosengart informed the court that he would be working to terminate the conservatorship.[293] Later that day, Spears publicly endorsed the #FreeBritney movement for the first time, using the hashtag in a caption on an Instagram post. She mentioned feeling "blessed" after earning "real representation", referring to Judge Penny's decision to allow her to choose her own counsel.[294]

On July 26, Rosengart filed a petition seeking to remove Jamie as conservator of Spears's estate and to replace him with Jason Rubin, a Certified Public Accountant (CPA) at Certified Strategies Inc. in Woodland Hills, California.[295] On August 12, Jamie agreed to step down as conservator at some future date, with his lawyers stating that he wanted "an orderly transition to a new conservator".[296] On September 7, Jamie filed a petition to end the conservatorship.[297] Five days later, Spears announced her engagement to her longtime boyfriend, Sam Asghari, through an Instagram post.[298] On September 29, Judge Penny suspended Jamie as conservator of Spears's estate, with accountant John Zabel replacing him on a temporary basis.[299] On November 12, Judge Penny terminated the conservatorship.[6]

2022–present: Book deal, third marriage, and "Hold Me Closer"

On February 21, 2022, it was reported that Spears signed a $15 million book deal for her upcoming memoir,[300] one of the biggest book deals of all time.[301] Two months later, she announced her pregnancy with Asghari's child,[302] which ended in a miscarriage the following month.[303] The couple married on June 9 at her home in Thousand Oaks, Los Angeles.[304] None of Spears's immediate family (including her parents, sister, and brother) were invited; her two sons did not attend.[305][306] Spears's first husband, Jason Alexander, attempted to crash the wedding by breaking into her home, armed with a knife, but was arrested.[307] Spears had a three-year restraining order against him.[308] On August 26, Spears and English musician Elton John released the duet "Hold Me Closer", a remake of John's 1972 single "Tiny Dancer".[309][310] It was Spears's first musical release since the termination of her conservatorship.[311] "Hold Me Closer" debuted at number six on the US Billboard Hot 100, becoming her 14th top-ten single and her highest-charting song in the chart since "Scream & Shout" (2012).[312] It debuted at number three on the UK Singles Chart.[313]

Since the termination of her conservatorship, Spears's personal life, social media presence, and overall well-being have been subject to renewed media interest and fan speculation, giving rise to conspiracy theories.[314] On January 24, 2023, deputies from the Ventura County Sheriff's Office performed a welfare check at Spears's residence after receiving several calls from fans who were concerned after she deleted her Instagram account. A spokesperson for the Sheriff's Department stated that Spears "was safe and in no danger." Spears addressed the incident on her Twitter account, asking fans to respect her privacy.[315]

Artistry

Influences

Spears has cited Madonna, Janet Jackson, and Whitney Houston as major influences, her "three favorite artists" as a child, whom she would "sing along to ... day and night in [her] living room"; Houston's "I Have Nothing" was the song she auditioned to that landed her record deal with Jive Records.[316] Spears also named Mariah Carey as "one of the main reasons I started singing".[317] Throughout her career, Spears has drawn frequent comparisons to Madonna and Jackson in particular, in terms of vocals, choreography, and stage presence. According to Spears: "I know when I was younger, I looked up to people ... like, you know, Janet Jackson and Madonna. And they were major inspirations for me. But I also had my own identity and I knew who I was."[318]

In the 2002 book Madonnastyle by Carol Clerk, she is quoted saying: "I have been a huge fan of Madonna since I was a little girl. She's the person that I've really looked up to. I would really, really like to be a legend like Madonna."[319] Spears cited "That's the Way Love Goes" as the inspiration for her song "Touch of My Hand" from her album In the Zone, saying "I like to compare it to 'That's the Way Love Goes,' kind of a Janet Jackson thing."[320] She also said her song "Just Luv Me" from her Glory album also reminded her of "That's the Way Love Goes".[321]

After meeting Spears face to face, Janet Jackson stated: "she said to me, 'I'm such a big fan; I really admire you.' That's so flattering. Everyone gets inspiration from some place. And it's awesome to see someone else coming up who's dancing and singing, and seeing how all these kids relate to her. A lot of people put it down, but what she does is a positive thing."[322] Madonna said of Spears in the documentary Britney: For the Record: "I admire her talent as an artist ... There are aspects about her that I recognize in myself when I first started out in my career".[323] Spears has also named Michael Jackson, Mariah Carey, Sheryl Crow, Otis Redding, Shania Twain, Brandy, Beyoncé, Natalie Imbruglia, Cher, and Prince as inspirations,[324][325][326][327][328] and younger artists such as Selena Gomez and Ariana Grande.[329][330]

Musical style

Spears is described as a pop artist[19] and generally explores the genre in the form of dance-pop.[331][332][333] Following her debut, she was credited with influencing the revival of teen pop in the late 1990s.[334] Rob Sheffield of Rolling Stone wrote: "Spears carries on the classic archetype of the rock & roll teen queen, the dungaree doll, the angel baby who just has to make a scene."[335] In a review of ...Baby One More Time, Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic described her music as a "blend of infectious, rap-inflected dance-pop and smooth balladry."[336] Oops!... I Did It Again saw Spears working with several R&B producers to create "a combination of bubblegum, urban soul, and raga".[337] Her third studio album, Britney derived from the teen pop niche "[r]hythmically and melodically", but was described as "sharper, tougher than what came before", incorporating genres such as R&B, disco, and funk.[67][338]

Spears has explored and heavily incorporated the genres of electropop[339][340] and dance music in her records, as well as influences of urban and hip hop, which are most present on In the Zone and Blackout. In the Zone also experiments with Euro trance, reggae, and Middle Eastern music.[340][341][342] Femme Fatale and Britney Jean were also heavily influenced by electronic music genres.[343][344] Spears's ninth studio album Glory is more eclectic and experimental than her previous released work. She commented that it "took a lot of time ... it's really different ... there are like two or three songs that go in the direction of more urban that I've wanted to do for a long time now, and I just haven't really done that."[345]

...Baby One More Time and Oops!... I Did It Again address themes such as love and relationships from a teenager's point of view.[346][347] Following the massive commercial success of her first two studio albums, Spears's team and producers wanted to maintain the formula that took her to the top of the charts.[346] Spears, however, was no longer satisfied with the sound and themes covered on her records. She co-wrote five songs and choose each track's producer on her third studio album, Britney, which lyrics address the subjects of reaching adulthood, sexuality, and self-discovery.[67][346][338] Sex, dancing, freedom, and love continued to be Spears's music main subjects on her subsequent albums.[341][342][344][343] Her fifth studio effort, Blackout, also addresses issues such as fame and media scrutiny, including on the song "Piece of Me".[342][348]

Spears's music has also been noted for some catchphrases. The opening in her debut single "...Baby One More Time", "Oh, baby baby" is considered to be one of her signature lines and has been parodied in the media by various artists such as Nicole Scherzinger and Ariana Grande.[349] It has been used in variating forms throughout her music, such as simply, "baby" and "oh baby", as well as the Blackout track, "Ooh Ooh Baby". On the initial development of "...Baby One More Time", Barry Weiss noted Spears's inception of the catchphrase from her strange ad-libbing during the recording of the song. He commented further, "We thought it was really weird at first. It was strange. It was not the way Max wrote it. But it worked! We thought it could be a really good opening salvo for her."[350] The opening line in "Gimme More", "It's Britney, bitch" has become another signature phrase.[351] An early review of Blackout suggested the phrase was "simply laughable".[351] Amy Roberts of Bustle called it "an indelible cultural turning point, transforming a frenetic, floundering moment in the superstars career to one of strength and empowerment".[351]

Voice

Spears is a soprano.[356][357][358][359] Other sources state that she possesses a contralto vocal range.[360][361] Prior to her breakthrough success, she is described as having sung "much deeper than her highly recognizable trademark voice of today", with Eric Foster White, who worked with Spears on her debut album ...Baby One More Time, being cited as "[shaping] her voice over the course of a month" upon being signed to Jive Records "to where it is today—distinctively, unmistakably Britney".[35] Rami Yacoub who co-produced Spears's debut album with lyricist Max Martin, commented, "I know from Denniz Pop and Max's previous productions, when we do songs, there's kind of a nasal thing. With N' Sync and the Backstreet Boys, we had to push for that mid-nasal voice. When Britney did that, she got this kind of raspy, sexy voice."[362]

Guy Blackman of The Age wrote that "[t]he thing about Spears, though, is that her biggest songs, no matter how committee-created or impossibly polished, have always been convincing because of her delivery, her commitment and her presence. ... Spears expresses perfectly the conflicting urges of adolescence, the tension between chastity and sexual experience, between hedonism and responsibility, between confidence and vulnerability."[363] Producer William Orbit, who worked with Spears on her album Britney Jean, stated regarding her vocals: "[Britney] didn't get so big just because [she] put on great shows; [she] got to be that way because [her voice is] unique: you hear two words and you know who is singing".[364]

Spears has also been criticized for her reliance on Auto-Tune[365] and her vocals being "over-processed" on records.[366] Erlewine criticized Spears's singing abilities in a review of her Blackout album, stating: "Never the greatest vocalist, her thin squawk could be dismissed early in her career as an adolescent learning the ropes, but nearly a decade later her singing hasn't gotten any better, even if the studio tools to masquerade her weaknesses have."[342] Joan Anderman of The Boston Globe remarked that "Spears sounds robotic, nearly inhuman, on her records, so processed is her voice by digital pitch-shifters and synthesizers."[367]

Kayla Upadhyaya of The Michigan Daily has provided a different point of view, stating: "Auto-tuned and over-processed vocals define [Spears]'s voice as an artist, and in her music, auto-tune isn't so much a gimmick as it is an instrument used to highlight, contort and make a statement."[368] Adam Markovitz of Entertainment Weekly opines that "Spears is no technical singer, that's for sure. But backed by Martin and Dr. Luke's wall of pound, her vocals melt into a mix of babytalk coo and coital panting that is, in its own overprocessed way, just as iconic and propulsive as Michael Jackson's yips or Eminem's snarls."[369]

Stage performances and videos

Spears is known for her stage performances, particularly the elaborate dance routines which incorporate "belly-dancing and tempered erotic moves" that are credited with influencing "dance-heavy acts" such as Danity Kane and the Pussycat Dolls.[370][371] Rolling Stone readers voted Spears their second-favorite dancing musician.[372] Spears is described as being much more shy than her stage persona suggests.[96][373][374] She said that performing is "a boost to [her] confidence. It's like an alter-ego type thing. Something clicks and I go and turn into this different person. I think it's kind of a gift to be able to do that."[375] Her 2000, 2001, and 2003 MTV Video Music Awards performances were lauded,[376] while her 2007 presentation was widely panned by critics, as she "teetered through her dance steps and mouthed only occasional words".[377] Billboard called her 2016 "comeback" performance at the show "an effective, but not entirely glorious, bid to regain pop superstardom".[358]

After her knee injuries and personal problems, Spears's "showmanship" and dance abilities came under criticism.[370][378] Serge F. Kovaleski of The New York Times watched her Las Vegas concert residency in 2016 and stated: "Once a fluid, natural dancer, Ms. Spears can appear stiff, even robotic, today, relying on flailing arms and flashy sets."[379] Las Vegas Sun's Robin Leach seemed more impressed over Spears's efforts on the concert by saying that she delivered a "flawless performance" on the residency's opening night.[380]

It has been widely reported that Spears lip-syncs during live performances,[371][381][382] which often prompts criticism from music critics and concert goers.[378][383][384] Some, however, claimed that, although she "got plenty of digital support", she "doesn't merely lip-sync" during her live shows.[385] In 2016, Sabrina Weiss of Refinery29 referred to her lip-syncing as a "well-known fact that's not even taboo anymore."[386] Noting on the prevalence of lip-syncing, the Los Angeles Daily News opined: "In the context of a Britney Spears concert, does it really matter? ... you [just] go for the somewhat-ridiculous spectacle of it all".[387] Spears herself has commented on the topic, arguing: "Because I'm dancing so much, I do have a little bit of playback, but there's a mixture of my voice and the playback. ... It really pisses me off because I'm busting my ass out there and singing at the same time and nobody ever gives me credit for it".[381]

In 2012, VH1 ranked Spears as the fourth Greatest Woman of the Video Era,[388] while Billboard ranked her as the eight Greatest Music Video Artist of All Time in 2020, explaining: "The storylines, the dancing, the outfits. Right from the start, the pop princess established the lengths of her creativity with some of the most memorable videos of the last three decades."[389] She has been retroactively noted as the pioneer for her early career videography.[390] She conceptualized the "iconic Catholic schoolgirl and cheerleader motif" in the "...Baby One More Time" video, rejecting the animation video idea. She also made the "Oops!... I Did It Again" video "dance-centric rather than space-centric as her producers suggested". She also used her dancer's intuition to help select the beats for each track.[390]

Public image

Upon launching her music career with ...Baby One More Time, Spears was labeled a teen idol,[392] and Rolling Stone described her as "the latest model of a classic product: the unneurotic pop star who performs her duties with vaudevillian pluck and spokesmodel charm."[29] The April 1999 cover of Rolling Stone featured Spears lying on her bed, wearing an open top revealing her bra, and shorts, while clutching a Teletubby.[29][393] The American Family Association (AFA) referred to the shoot as "a disturbing mix of childhood innocence and adult sexuality" and called on "God-loving Americans to boycott stores selling Britney's albums." Spears addressed the outcry, commenting: "What's the big deal? I have strong morals. ... I'd do it again. I thought the pictures were fine. And I was tired of being compared to Debbie Gibson and all of this bubblegum pop all the time."[394] Shortly prior, Spears had announced publicly she would remain abstinent until marriage.[30][395]

An early criticism of Spears dismissed her as a "manufactured pop star, the product of a Swedish songwriting factory that had no real hand in either her music or her persona", which Vox editor Constance Grady assesses as being perpetuated from the fact that Spears debuted in the late 1990s, when music was dominated by rockism, that prizes "so-called authenticity and grittiness of rock above all else". Spears's "slick, breezy pop was an affront to rockist sensibilities, and claiming that Spears was fake was an easy way to dismiss her." Ron Levy for Rolling Stone noted that "I have to tell you, if the record company could have created more than one Britney Spears, they would have done it, and they tried!"[390]

Billboard opined that, by the time Spears released her sophomore album Oops!... I Did It Again, "There was a shift occurring in both the music and her public image: She was sharper, sexier and singing about more grown-up fare, setting the stage for 2001's Britney, which shed her innocent skin and ushered her into adulthood."[396] Britney's lead single "I'm a Slave 4 U" and its music video were also credited for distancing her from her previous "wholesome bubblegum star" image.[397][398] Stephen Thomas Erlewine of AllMusic remarked, "If 2001's Britney was a transitional album, capturing Spears at the point when she wasn't a girl and not yet a woman, its 2003 follow-up, In the Zone, is where she has finally completed that journey and turned into Britney, the Adult Woman." Erlewine likened Spears to fellow singer Christina Aguilera, explaining that both equated "maturity with transparent sexuality and the pounding sounds of nightclubs".[341] Brittany Spanos of LA Weekly stated that Spears "set the bar for the 'adulthood' transition teen pop stars often struggle with".[399]

Spears's erratic behavior and personal problems during 2006–2008 were highly publicized[400] and affected both her career and public image.[342][401] Erlewine reflected on this period of her life, stating that "each new disaster [was] stripping away any residual sexiness in her public image".[342] In a 2008 article, Rolling Stone's Vanessa Grigoriadis described her much-publicized personal issues as "the most public downfall of any star in history".[401] Spears later received favorable media attention; Billboard opined that her appearance at the 2008 MTV Video Music Awards "was a picture of professionalism and poise" after her "disastrous" performance at the previous year's show,[402] while Business Insider ran an article on how she had "lost control of her life ... and then made an incredible career comeback".[403] Spears later reflected on this tumultuous period, saying: "I think I had to give myself more breaks through my career and take responsibility for my mental health. ... I wrote back then, that I was lost and didn't know what to do with myself. I was trying to please everyone around me because that's who I am deep inside. There are moments where I look back and think: 'What the hell was I thinking?'"[404]

In September 2002, Spears was placed at number eight on VH1's 100 Sexiest Artists list.[405] She was placed at number one on FHM's 100 Sexiest Women in the World list in 2004,[406] and, in December 2012, Complex ranked her 12th on its 100 Hottest Female Singers of All Time list.[407] Remarking upon her perceived image as a sex symbol, Spears stated: "When I'm on stage, that's my time to do my thing and go there and be that — and it's fun. It's exhilarating just to be something that you're not. And people tend to believe it."[346] In 2003, People magazine cited her as one of the 50 Most Beautiful People.[408]

Spears is recognized as a gay icon and was honored with the 2018 GLAAD Vanguard Award at the GLAAD Media Awards for her role in "accelerating acceptance for the LGBTQ community".[248] Spears addressed the "unwavering loyalty" and "lack of judgment" of her LGBTQ fans in Billboard's Love Letters to the LGBTQ Community. She said: "Your stories are what inspire me, bring me joy, and make me and my sons strive to be better people."[409] Manuel Betancourt of Vice magazine wrote about the "queer adoration", especially of gay men, on Spears, and said that "Where other gay icons exude self-possession, Spears' fragile resilience has made her an even more fascinating role model, closer to Judy Garland than to Lady Gaga ... she's a glittering mirror ball, a fractured reflection of those men on the dance floor back onto themselves."[373] HuffPost's Ben Appel attributed Spears's status as a gay icon to "her oh-so-innocent/"not that innocent" Monroe-like sensuality, her sweet, almost saccharine nature, her beyond basic but addictive pop songs, her dance moves, her phoenix-out-of-the-fire comeback from a series of mental health crises, and her unmistakable tenderness. Britney is camp. She is a fashion plate. A doll. Britney is a drag queen."[410]

Since her early years in the public eye, Spears has been a tabloid fixture and a paparazzi target.[396][395][411] Steve Huey of AllMusic remarked that "among female singers of [Spears's] era ... her celebrity star power was rivaled only by Jennifer Lopez."[395] 'Britney Spears' was Yahoo!'s most popular search term between 2005 and 2008, and has been in a total of seven different years.[412] Spears was named as Most Searched Person in the Guinness World Records book edition 2007 and 2009.[413] She was later named as the most searched person of the decade 2000–2009.[414]

As a public figure, Spears "has never been known to her fans as a politically active, committed—or even aware—entertainer."[333] In a 2003 interview with Tucker Carlson, she commented on President George W. Bush and the Iraq War, saying that "we should just trust our president in every decision that he makes ... and be faithful in what happens".[415] Michael Moore included the footage of Spears's answer in his "anti-Bush" documentary Fahrenheit 9/11, which, according to The Washington Times's James Frazier, presented her "as an example of a naive American blindly trusting a dishonest commander in chief" and fueled the "urban legend" of a "conservative" Spears. Frazier also said that "the few positions she has taken can hardly be considered conservative", such as supporting same-sex marriage.[333] In 2016, Spears posted pictures of a meeting with Hillary Clinton on social media. She described Clinton as "an inspiration and [a] beautiful voice for women around the world".[416]

In December 2017, Spears publicly showed support for the DREAM Act in the wake of the announcement that Donald Trump would end the DACA policy, which previously granted undocumented immigrants who came to the country as minors a renewable two-year period of deferred action from deportation. She posted a photo of herself on social media wearing a black T-shirt that reads "We Are All Dreamers" in white letters. The caption read, "Tell Congress to pass the #DreamAct".[417]

In 2020, amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, Spears posted an image on Instagram stating, "During this time of isolation ... We will feed each other, redistribute wealth, strike. We will understand our own importance from the places we must stay", along with three emoji roses, "a symbol commonly used by the Democratic Socialists of America".[418] She later voiced support for the Black Lives Matter movement and George Floyd protests in the wake of his murder, saying: "My heart breaks for my friends in the black community ... and for everything going on in our country. Right now I think we should all do what we can to listen, learn, do better, and use our voices for good."[419]

On September 15, 2021, Spears was named one of the 100 most influential people of 2021 by Time magazine. A few days before the editors's list was released, Spears was put at the top of the readers voting list of which personalities should be included on the annual Time 100 list. Deemed an icon of 2021, editors highlighted the impact of her fight against her conservatorship as well as of the #FreeBritney movement.[420][421] In October 2021, Spears thanked her fans and the #FreeBritney movement for "freeing me from my conservatorship".[422]

Legacy

Referred to as the "Princess of Pop",[423][424] Spears was credited as one of the "driving force[s] behind the return of teen pop in the late 1990s".[395][334] Rolling Stone's Stacy Lambe explained that she "help[ed] to usher in a new era for the genre that had gone dormant in the decade that followed New Kids on the Block. ... Spears would lead an army of pop stars ... built on slick Max Martin productions, plenty of sexual innuendo and dance-heavy performances. [She became] one of the most successful artists of all time—and a cautionary tale for a generation, whether they paid attention or not."[424] In a 2021 article for Time, Maura Johnston opined that "Spears' legacy as a pop artist is complex, made up of dazzling musical heights and music-business-borne lows". Johnston also commented: "While Spears' catalog is part of the canon that defines the first 20 years of this millennium, one hopes that her public struggles, and the strength she's shown while enduring them, will lead to her cementing her true legacy: Reshaping the machine that turns those songs into cultural touchstones."[425]

Glamour magazine contributor Christopher Rosa described her as "one of pop music's defining voices. ... When she emerged onto the scene in 1998 with ...Baby One More Time, the world hadn't seen a performer like her. Not since Madonna had a female artist affected the genre so profoundly."[426] Billboard's Robert Kelly observed that Spears's "sexy and coy" vocals on her debut single "...Baby One More Time" "kicked off a new era of pop vocal stylings that would influence countless artists to come."[427] In 2020, Rolling Stone ranked the song at number one on a list of the 100 Greatest Debut Singles of All Time and Rob Sheffield described it as "One of those pop manifestos that announces a new sound, a new era, a new century. But most of all, a new star ... With "...Baby One More Time", [Spears] changed the sound of pop forever: It's Britney, bitch. Nothing was ever the same."[428]

Spears was at the forefront of the female teen pop explosion starting in 1999 and extending through the 2000s, leading the pack of Christina Aguilera, Jessica Simpson, and Mandy Moore.[429] All of these performers had been developing material in 1998, but the market changed dramatically in December 1998 when Spears's single and video were charting highly. RCA Records quickly signed Aguilera and rushed her debut single to capitalize on Spears's success, producing the hit single "Genie in a Bottle" in June 1999 and Aguilera's debut album a few months later.[430] Her album sold millions but not as many as Spears's.[431] Simpson consciously modeled her persona as more mature than Spears; her "I Wanna Love You Forever" charted in September 1999, and her album Sweet Kisses followed shortly after.[432][433] Moore's first single, "Candy", hit the airwaves a month before Simpson's single, but it did not perform as well on the charts; Moore was often seen as less accomplished than Spears and the others, coming in fourth of the "pop princesses".[434][435] Fueling media stories about their competition for first place, Spears and Aguilera traded barbs but also compliments through the 2000s.[436]

Alim Kheraj of Dazed called Spears "one of pop's most important pioneers".[437] After eighteen years as a performer, Billboard described her as having "earned her title as one of pop's reigning queens. Since her early days as a Mouseketeer, [Spears] has pushed the boundaries of 21st century sounds, paving the way for a generation of artists to shamelessly embrace glossy pop and redefine how one can accrue consistent success in the music industry."[396] Entertainment Weekly's Adam Markovitz described Spears as "an American institution, as deeply sacred and messed up as pro wrestling or the filibuster."[369] In 2012, she was ranked as the fourth VH1's 50 Greatest Women of the Video Era show list.[388] VH1 also cited her among its choices on the 100 Greatest Women in Music in 2012[438] and the 200 Greatest Pop Culture Icons in 2003.[439] In 2020, Billboard ranked her eight on its 100 Greatest Music Video Artists of all-time list.[389]

Spears and her work have influenced various artists including Katy Perry,[440] Meghan Trainor,[441] Demi Lovato,[440] Kelly Key,[442] Kristinia DeBarge,[443] Little Boots,[444] Charli XCX,[445] Marina Diamandis,[446] the Weeknd,[447] Tegan and Sara,[448] Pixie Lott,[449] Grimes,[450] Selena Gomez,[451] Hailee Steinfeld,[452] Pabllo Vittar,[453] Tinashe,[454] Victoria Justice,[455] Cassie,[456] Leah Wellbaum of Slothrust,[457] the Saturdays,[458] Normani,[459] Miley Cyrus,[460] Cheryl,[461] Lana Del Rey,[462] Ava Max,[463] Billie Eilish,[464] Sam Smith,[465] and Rina Sawayama.[466] During the 2011 MTV Video Music Awards, Lady Gaga said that Spears "taught us all how to be fearless, and the industry wouldn't be the same without her."[168] Gaga has also cited Spears as an influence, calling her "the most provocative performer of my time."[467]